On this page

Flare-On 12 Challenges 1-4

1. Drill Baby Drill

We get a PyGame application about a baby drilling underground to recover lost teddy bears.

Looking at the source, we find a function named GenerateFlagText:

def GenerateFlagText(sum):

key = sum >> 8

encoded = "\xd0\xc7\xdf\xdb\xd4\xd0\xd4\xdc\xe3\xdb\xd1\xcd\x9f\xb5\xa7\xa7\xa0\xac\xa3\xb4\x88\xaf\xa6\xaa\xbe\xa8\xe3\xa0\xbe\xff\xb1\xbc\xb9"

plaintext = []

for i in range(0, len(encoded)):

plaintext.append(chr(ord(encoded[i]) ^ (key+i)))

return ''.join(plaintext)

A quick search shows it's called once, using bear_sum as the argument:

if bear_mode:

screen.blit(bearimage, (player.rect.x, screen_height - tile_size))

if current_level == len(LevelNames) - 1 and not victory_mode:

victory_mode = True

flag_text = GenerateFlagText(bear_sum)

print("Your Flag: " + flag_text)

Notice that GenerateFlagText is called only on the final level. Just above that we can see how bear_sum is computed:

if player.hitBear():

player.drill.retract()

bear_sum *= player.x

bear_mode = True

Each time the player collects a bear, bear_sum is multiplied by the baby's current x position.

Since Flare-On flags end up with "@flare-on.com", we can write a short bruteforce script over sum values until the decrypted text contains that substring. To bound the search, we need to know the range of bear_sum.

Searching for player.x leads us to AttemptPlayerMove:

def AttemptPlayerMove(dx, dy):

newx = player.x + dx

# Can only move within screen bounds

if newx < 0 or newx >= tiles_width:

return False

# Can only move side to side when drill is not engaged

if dx != 0 and player.drill.drillEngaged():

return False

# Operate drill if they moved up or down

if dy < 0:

player.drill.retract()

elif dy > 0:

DrillTile()

player.move(dx)

return True

This means player.x is always within: 0 <= x < tiles_width. tiles_width is defined as:

screen_width = 800

screen_height = 600

tile_size = 40

tiles_width = screen_width // tile_size

So tiles_width = 800 // 40 = 20, and therefore x can be at most 19.

We saw that if player.hitBear() returns True, bear_mode is set to True. Searching for bear_mode brings us to:

if bear_mode:

bear_mode = False

next_level_mode = True

So finiding a bear automatically moves you to the next level. As there are 5 levels:

LevelNames = [

'California',

'Ohio',

'Death Valley',

'Mexico',

'The Grand Canyon'

]

We can conclude that bear_sum is the product of 5 x positions: 0 <= bear_sum < 19^5.

We can write a Python script bruteforcing that range:

def GenerateFlagText(sum):

key = sum >> 8

encoded = "\xd0\xc7\xdf\xdb\xd4\xd0\xd4\xdc\xe3\xdb\xd1\xcd...." # truncated

plaintext = []

for i in range(0, len(encoded)):

plaintext.append(chr(ord(encoded[i]) ^ (key+i)))

return ''.join(plaintext)

for i in range(19 ** 5):

flag = GenerateFlagText(i)

if "@flare-on.com" in flag:

print(flag)

break

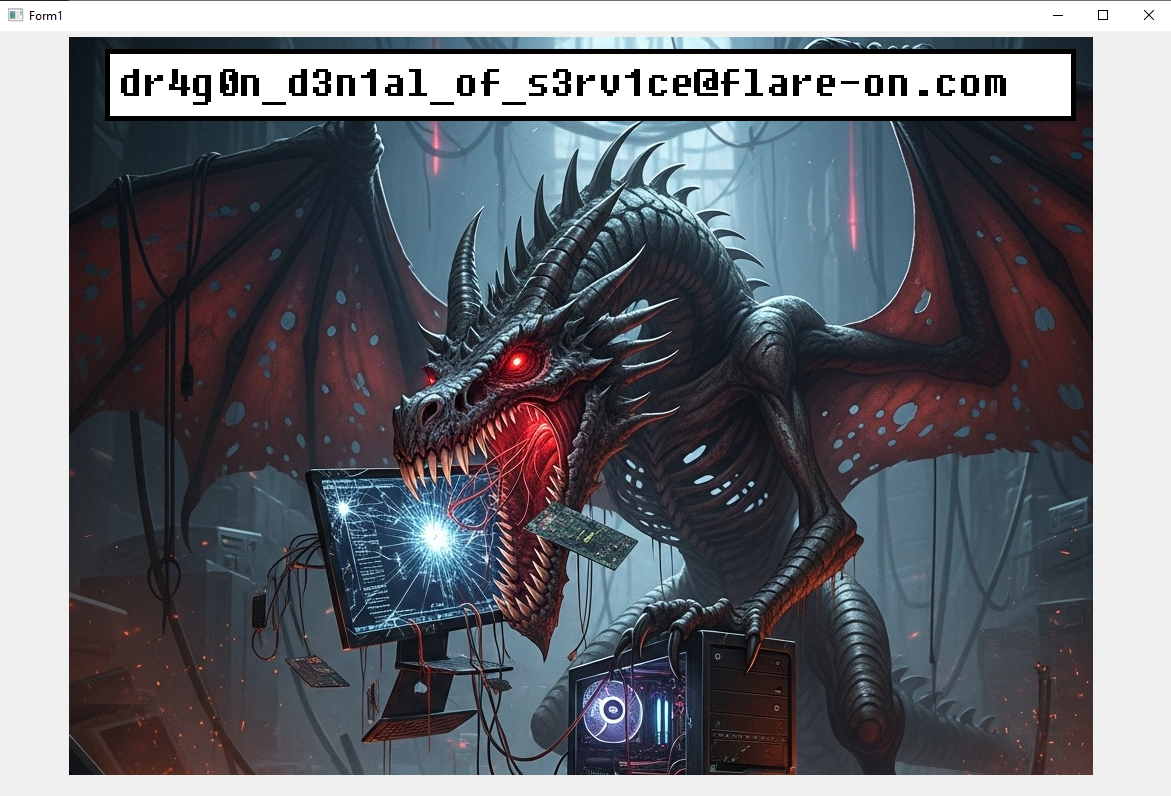

Running the script yields the flag:

PS C:\Users\user\Desktop\Flare Writeup\1> py solver.py

[email protected]

2. Project Chimera

We are provided with a Python file project_chimera.py

import zlib

import marshal

# These are my encrypted instructions for the Sequencer.

encrypted_sequencer_data = b'x\x9cm\x96K\xcf....' # truncated

print(f"Booting up {f"Project Chimera"} from Dr. Khem's journal...")

# Activate the Genetic Sequencer. From here, the process is automated.

sequencer_code = zlib.decompress(encrypted_sequencer_data)

exec(marshal.loads(sequencer_code))

The code is fairly simple. It takes a zlib compressed blob, decompresses it into a Python marshalled code object and executes it using exec.

To decompile the bytecode, we first need a valid compiled Python file (.pyc). A .pyc file is a 16-byte header followed by the marshalled code object. Since the code executed correctly on my Python install, I assumed it was produced by the same interpreter version, so I reused that interpreter's MAGIC_NUMBER. Under PEP 552, the header layout is:

- 4 bytes: magic number (versioning the bytecode and pyc format)

- 4 bytes: flags (LSB set -> hash-based pyc; second LSB clear -> unchecked mode)

- 8 bytes: hash field (ignored in unchecked mode, so zeros are fine)

- rest: the marshalled code object

We can generate it with the following function:

def codeobj_to_pyc(code_obj) -> bytes:

magic = importlib.util.MAGIC_NUMBER

flags = 0x01

hash_bytes = b"\x00" * 8

header = magic + struct.pack("<I", flags) + hash_bytes

payload = marshal.dumps(code_obj)

return header + payload

Now we can decompile the resulting .pyc file. For this task I used PyLingual. The decompiled code turns out to be a second stage loader:

import base64

import zlib

import marshal

import types

encoded_catalyst_strand = b'c$|e+O>7&-6`m!Rzak~llE....' # truncated

print('--- Calibrating Genetic Sequencer ---')

print('Decoding catalyst DNA strand...')

compressed_catalyst = base64.b85decode(encoded_catalyst_strand)

marshalled_genetic_code = zlib.decompress(compressed_catalyst)

catalyst_code_object = marshal.loads(marshalled_genetic_code)

print('Synthesizing Catalyst Serum...')

catalyst_injection_function = types.FunctionType(catalyst_code_object, globals())

catalyst_injection_function()

Following the same path, decompiling the payload finally exposes the real challenge logic:

import os

import sys

import emoji

import random

import asyncio

import cowsay

import pyjokes

import art

from arc4 import ARC4

async def activate_catalyst():

LEAD_RESEARCHER_SIGNATURE = b'm\x1b@I\x1dAoe@\x07ZF[BL\rN\n\x0cS'

ENCRYPTED_CHIMERA_FORMULA = b'r2b-\r\x9e\xf2\x1fp\x185\x82....' # truncated

print('--- Catalyst Serum Injected ---')

print("Verifying Lead Researcher's credentials via biometric scan...")

current_user = os.getlogin().encode()

user_signature = bytes((c ^ i + 42 for i, c in enumerate(current_user)))

await asyncio.sleep(0.01)

status = 'pending'

if status == 'pending':

if user_signature == LEAD_RESEARCHER_SIGNATURE:

art.tprint('AUTHENTICATION SUCCESS', font='small')

print('Biometric scan MATCH. Identity confirmed as Lead Researcher.')

print('Finalizing Project Chimera...')

arc4_decipher = ARC4(current_user)

decrypted_formula = arc4_decipher.decrypt(ENCRYPTED_CHIMERA_FORMULA).decode()

cowsay.cow('I am alive! The secret formula is:\n' + decrypted_formula)

else:

art.tprint('AUTHENTICATION FAILED', font='small')

print('Impostor detected, my genius cannot be replicated!')

print('The resulting specimen has developed an unexpected, and frankly useless, sense of humor.')

joke = pyjokes.get_joke(language='en', category='all')

animals = cowsay.char_names[1:]

print(cowsay.get_output_string(random.choice(animals), pyjokes.get_joke()))

sys.exit(1)

else:

if False:

pass

print('System error: Unknown experimental state.')

asyncio.run(activate_catalyst())

The code XORs each byte of current_user with (its index + 42). If the result matches LEAD_RESEARCHER_SIGNATURE we use current_user as the RC4 key to decrypt the ciphertext. Recovering the required username from the signature is trivial:

Python 3.12.0 (tags/v3.12.0:0fb18b0, Oct 2 2023, 13:03:39)

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

Ctrl click to launch VS Code Native REPL

>>> SIGNATURE = b'm\x1b@I\x1dAoe@\x07ZF[BL\rN\n\x0cS'

>>> current_user = bytes((c ^ i + 42 for i, c in enumerate(SIGNATURE)))

>>> current_user

b'G0ld3n_Tr4nsmut4t10n'

Having found the correct current_user, we can decrypt the ciphertext and get the flag:

Python 3.12.0 (tags/v3.12.0:0fb18b0, Oct 2 2023, 13:03:39)

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

Ctrl click to launch VS Code Native REPL

>>> from arc4 import ARC4

>>> current_user = b"G0ld3n_Tr4nsmut4t10n"

>>> ENCRYPTED_CHIMERA_FORMULA = b'r2b-\r\x9e\xf2\x1fp\x185\x82\xcf' # truncated

>>> arc4_decipher = ARC4(current_user)

>>> decrypted_formula = arc4_decipher.decrypt(ENCRYPTED_CHIMERA_FORMULA).decode()

>>> decrypted_formula

'[email protected]'

3. Pretty Devilish File

We are provided with a file pretty_devilish_file.pdf. I tried opening it with several PDF readers but that didn't work, so I assumed the file was malformed.

The PDF is pretty small. The relevant parts are:

- Object 4, which contains a compressed stream:

4 0 obj

<</Length 320/Filter /FlateDecode>>stream

.............................................

.............................................

.............................................

endstream

- The trailer, which references an encryption dictionary:

trailer <<

...

/Encrypt 7 0 R

>>

I used qpdf to try and fix the PDF:

qpdf --linearize pretty_devilish_file.pdf less_of_a_devilish_file.pdf

The repaired output no longer included the /Encrypt entry. At this point we can use qpdf again to decompress the stream (which qpdf renumbered to object 8):

qpdf --show-object=8 --filtered-stream-data less_of_a_devilish_file.pdf > obj8_uncompressed.bin

q 612 0 0 10 0 -10 cm

BI /W 37/H 1/CS/G/BPC 8/L 458/F[

/AHx

/DCT

]ID

ffd8ffe000104a464946000 # truncated

EI Q

q

BT

/ 140 Tf

10 10 Td

(Flare-On!)'

ET

Q

The hex string seems interesting. A quick Google search reveals that its first bytes, FF D8 FF E0, are a valid signature for JPEG files. Let's extract those hex bytes into a file and check it in Python:

Python 3.13.5 (tags/v3.13.5:6cb20a2, Jun 11 2025, 16:15:46)

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

Ctrl click to launch VS Code Native REPL

>>> from PIL import Image

>>> img = Image.open("image.jpg")

>>>

>>> pixels = img.load()

>>> width, height = img.size

>>> width, height

(37, 1)

37x1.. could this be the flag?

>>> for y in range(height):

... for x in range(width):

... value = pixels[x, y]

... print(chr(value), end='')

...

[email protected]

4. Unholy Dragon

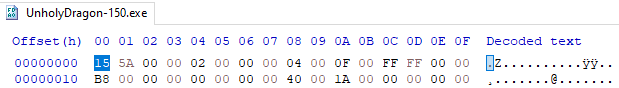

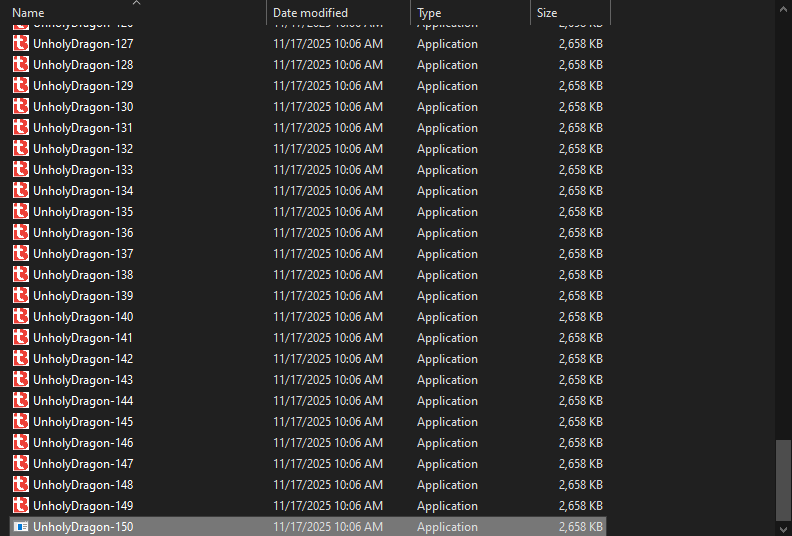

We are given an executable named UnholyDragon-150.exe, but running it fails. A quick look in a hex editor explains why:

The DOS header magic is corrupted. A PE file should start with the "MZ" signature (4D 5A). After patching the first byte to 4D, the program runs correctly. When executed, UnholyDragon-150.exe drops four additional executables into the same working directory:

We can compare these variants with fc.exe:

PS C:\Users\user\Desktop\Flare Writeup\4> fc.exe /b .\UnholyDragon-150.exe .\UnholyDragon-151.exe

Comparing files .\UnholyDragon-150.exe and .\UNHOLYDRAGON-151.EXE

001309C1: 5C 94

PS C:\Users\user\Desktop\Flare Writeup\4> fc.exe /b .\UnholyDragon-150.exe .\UnholyDragon-152.exe

Comparing files .\UnholyDragon-150.exe and .\UNHOLYDRAGON-152.EXE

001309C1: 5C 94

00286162: 0D 43

PS C:\Users\user\Desktop\Flare Writeup\4> fc.exe /b .\UnholyDragon-150.exe .\UnholyDragon-153.exe

Comparing files .\UnholyDragon-150.exe and .\UNHOLYDRAGON-153.EXE

001309C1: 5C 94

001B19A9: 84 96

00286162: 0D 43

PS C:\Users\user\Desktop\Flare Writeup\4> fc.exe /b .\UnholyDragon-150.exe .\UnholyDragon-154.exe

Comparing files .\UnholyDragon-150.exe and .\UNHOLYDRAGON-154.EXE

0006E8F8: FF 68

001309C1: 5C 94

001B19A9: 84 96

00286162: 0D 43

Each variant adds an additional single byte modification at some offset.

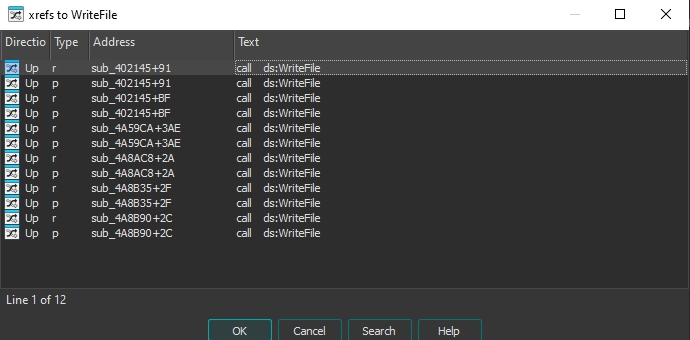

Running Procmon and filtering on UnholyDragon-* processes shows that each executable creates and launches the next variant. To understand how this happens, we can load UnholyDragon-150.exe in IDA and look at all the xrefs to WriteFile to try to work out where the change occurs.

One particularly interesting call is at sub_4A8AC8+2A:

void __stdcall sub_4A8AC8(int a1, LPCVOID lpBuffer, DWORD nNumberOfBytesToWrite)

{

DWORD v3; // edi

DWORD v4; // eax

int v5; // ecx

v3 = nNumberOfBytesToWrite;

if ( nNumberOfBytesToWrite )

{

if ( (*(_BYTE *)(a1 + 8) & 4) != 0 )

{

nNumberOfBytesToWrite = 0;

WriteFile(*(HANDLE *)a1, lpBuffer, v3, &nNumberOfBytesToWrite, 0);

v4 = nNumberOfBytesToWrite;

if ( nNumberOfBytesToWrite != v3 )

*(_DWORD *)(a1 + 36) = -2146828213;

*(_DWORD *)(a1 + 4) += v4;

}

else

{

v5 = *(_DWORD *)(a1 + 20);

*(_DWORD *)(a1 + 20) = v5 + nNumberOfBytesToWrite;

if ( (signed int)(v5 + v3) <= *(_DWORD *)(a1 + 12) )

sub_4A8962(v5 + *(_DWORD *)(a1 + 16), lpBuffer, v3);

}

}

}

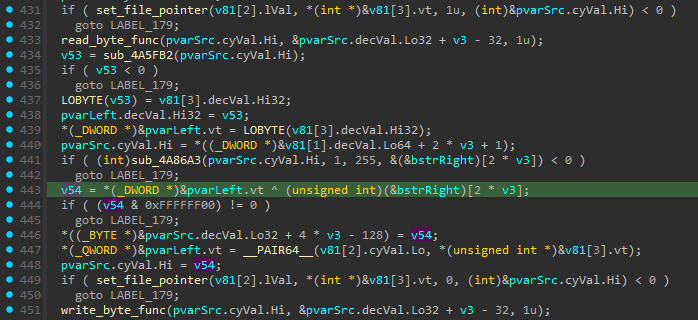

The number of bytes written is passed as nNumberOfBytesToWrite. This function has a single reference at sub_4A8F30+998:

sub_4A8AC8(pvarSrc.cyVal.Hi, &pvarSrc.decVal.Lo32 + v3 - 32, 1u);

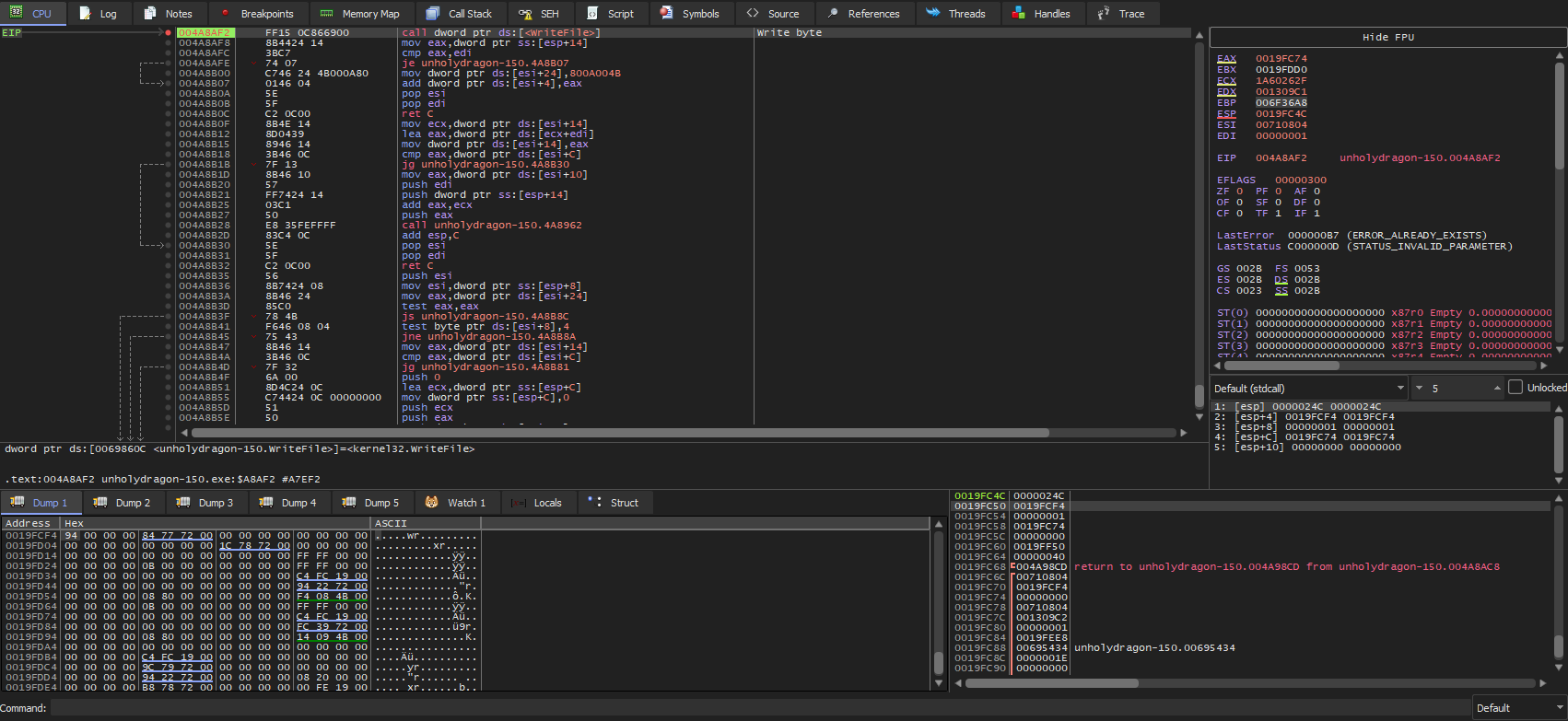

The function is called with nNumberOfBytesToWrite = 1. This matches the single byte modifications we see in the file diffs. We can verify this in x64dbg by placing a breakpoint at 0x4A8AF2 (the WriteFile call). In 32-bit stdcall, the second argument to WriteFile (the buffer pointer) is at [esp+4] (before entry).

Inspecting the buffer shows it contains 0x94, exactly the byte written to in UnholyDragon-151.exe. Doing some backward analysis from the function call we get a (somewhat) clearer picture of what's happening.

The file pointer is moved to some position.

One byte is read from that position.

That byte is XORed with another value.

The result is written back to the same location.

Placing a breakpoint in UnholyDragon-150.exe at the XOR instruction, 0x4A987A, shows that the original byte is XORed with C8. Doing the same in UnholyDragon-151.exe shows it's XORed with a different value. So the XOR key changes between variants.

How does it decide where to move the file pointer and which value to XOR with? Are the these single byte modifications feeding back into the logic? We could keep reversing but the data flow seems difficult to track. Looking at the import table we can see it imports GetFullPathNameW, perhaps the variant number determines the byte it changes? Should be simple enough to test.

Let's rename UnholyDragon-151.exe to UnholyDragon-150.exe and place 2 breakpoints in x64dbg.

- The call that sets the file pointer:

0x4A9821 - The XOR instruction:

0x4A987A

If the variant number alone controls the mutation, we would expect the byte at 001309C1 to be XORed with C8. Hitting the breakpoint shows that this is indeed the case. Since XOR operations are reversible, we can come to the conclusion that this process is reversible too! Letting the renamed UnholyDragon-151.exe run to completion should undo the mutation and give us back the original UnholyDragon-150.exe file.

PS C:\Users\user\Desktop\Flare Writeup\4> fc.exe /b .\UnholyDragon-150_original.exe .\UnholyDragon-151.exe

Comparing files .\UnholyDragon-150_original.exe and .\UNHOLYDRAGON-151.EXE

FC: no differences encountered

Since we know the mutations are filename driven and reversible, could it be that UnholyDragon-150.exe is the output of the same program? The name certainly suggests so. If UnholyDragon-150.exe is the result of running UnholyDragon-0.exe, renaming it to UnholyDragon-0.exe should give us the original UnholyDragon-0.exe file under the UnholyDragon-150.exe name.

It stopped at exactly 150. And just like our original 150 file, this one doesn't run either. Opening it in a hex editor reveals the same issue as our original file: corrupted byte at the DOS header.

After fixing it, running it reveals the flag: